It’s crowded at the top

Everest is so popular that its ecosystems suffer. Andrew Bain tries out camps built for local conditions.

On the slopes of Gokyo Ri, high in the Himalayas, it’s a race against cloud. The sun has just risen, briefly painting the mountain in amber light, but clouds are already marching through the valley and across the world’s highest peaks.

A stream of trekkers is heading for the 5360-metre summit of Gokyo Ri. Some turn back, beaten by the altitude and effort. Others walk a few steps then stop and bend over, hands on knees, fighting for breath. It’s the slowest race imaginable. Will we reach the summit before the cloud does? Or have we walked for eight days only to be robbed of one of the finest mountain views on the planet?

In the valleys below, Himalayan life goes on, indifferent to our ambitions. Prayer wheels spin in villages and monasteries, and prayer flags light hillsides like flowers, casting silent mantras to the heavens. Along the trails, porters hump impossible weights and yak teams resembling shaggy road trains amble between villages.

They are timeless scenes, yet the trekking landscape is in constant flux. In the 1950s, when the first expedition groups entered the region, mountaineers walked overland from the town of Banepa near Kathmandu. Today, trekkers fly into the town of Lukla, just 50 kilometres from the foot of Mount Everest. Internet cafes are sprinkled through villages and 3G base stations have been set up at Everest Base Camp, bringing wireless connection to the remotest of areas.

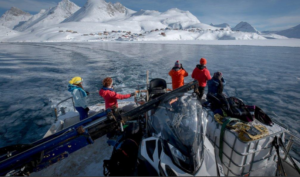

Recently, in a more back-to-the-future venture, Australian travel company World Expeditions has set up a series of permanent campsites on the two main trekking routes in the region: to Everest Base Camp and in the adjoining Gokyo valley.

I have come to the Everest region to hike with a group to Gokyo Ri, a mountain described by one trekking guidebook as having a “strong claim to be the best accessible viewpoint in Nepal”. From its summit, four of the world’s highest six mountains – Everest, Lhotse, Makalu and Cho Oyu – are visible, underscored by the longest glacier in the Himalayas. Many say Gokyo Ri has the finest of all views of Everest. Those credentials make even the more popular Everest Base Camp seem mundane in comparison. Already at Lukla, 2800 metres above sea level, breathing becomes heavier and we still have to climb another 2500 metres to the summit of Gokyo Ri. To acclimatise, we will ascend in baby steps, climbing just a few hundred metres each day in an attempt to prevent acute mountain sickness.

Though Namche Bazaar, the region’s major town, is less than 20 kilometres up the valley from Lukla, it will take us three days on a trail that’s busy with porters, trekkers and lines of tea houses. Beehives hang from cliff walls and the Dudh Kosi river rages through the mountains, its waters foaming as white as its translated name, Milk River, suggests. This waterway will be our guiding line for the next week, leading us to its glacial headwaters below Gokyo Ri.

Our homes each night to Namche are the new permanent tents, the first of their kind in Nepal. The six camps are set mostly a few hundred metres off the trail, just enough distance to bring an unlikely sense of remoteness – more than 32,000 people trekked into the Everest region last year – and they’re designed to address environmental concerns about tea-house trekking.

With purpose-built stone dining rooms, raised beds with five-centimetre-thick mattresses and tents large enough to stand in, each campsite has composting toilets and uses trapped rainwater. Yak dung is used for fires and kerosene for cooking, which eliminates the use of wood. In villages without permanent campsites, such as Gokyo and Namche Bazaar (where land is more costly than in Kathmandu), only tea houses that burn yak dung are used.

“We see deforestation as the biggest threat to the Everest region,” says the industry and trade manager of World Expeditions, Phil Wyndham. “And we see that tea-house trekking, with its use of wood stoves, only adds to that.”

We enter Everest’s orbit at Namche Bazaar. From the Sagarmatha National Park headquarters, on a knoll above town, comes our first glimpse of the world’s highest mountain. It’s a triangle of windswept rock set among an array of peaks – Lhotse, Ama Dablam, Thamserku – that appear even more impressive than their superstar neighbour. It’s little wonder the early mountaineer Bill Tilman called this scene “the grandest 30 miles [48 kilometres] of the Himalaya”.

Two hours beyond Namche, the trail reaches a welcome fork. Here, the Everest Base Camp path veers right and the Gokyo route turns left, thinning the crowds by more than half. We climb to the village of Mong La and into the cloud that’s descended over the Himalayas, as it will with clockwork regularity each afternoon. In the steep and narrow Gokyo valley, among pockets of skeletal rhododendrons and papery silver-birch forest, the string of villages all but disappears. The white noise of the Dudh Kosi rises hundreds of metres up the slopes. Porters sprint past, carrying 30 to 40 kilograms of weight on their heads, texting on their mobile phones as they go.

As the trail climbs through the valley, oxygen levels decrease accordingly and the first pains of altitude begin to scrape at my head. Waterfalls roar down one side of the valley but stand as frozen icy claws on the other. In the early mornings we look ahead to the white screen that is Cho Oyu – the world’s sixth-highest mountain – but in the afternoons we see only the grey guts of the clouds.

We make our final camp before Gokyo at the village of Machermo. Set at the head of a barren alpine tributary, with sharp-toothed Machermo Peak rising behind, it’s the most spectacular of the permanent camps. At an altitude of about 4450 metres, it’s also the coldest – everything from water bottles to toothpaste to the outside of my sleeping bag has frozen by morning.

The climb from Machermo to the tiny village of Gokyo is as wonderful as any of the peaks around us, ascending through rubble at the edge of the Ngozumpa Glacier – the longest glacier in the Himalayas – to the Gokyo Lakes. This chain of six lakes, strung together to form the headwaters of the Dudh Kosi, is the highest freshwater lake system in the world. At the first lake, ducks cruise across the iced surface and the black mass of Gokyo Ri appears ahead for the first time.

As cloud again rolls into the valley, we spend the afternoon holed up in a Gokyo tea house. We are supposedly conserving energy for the climb to Gokyo Ri the next morning, though at this altitude even simple movements are an effort. The next morning, in the tradition of summit days, we begin the climb before dawn, crossing an iced causeway at the head of the turquoise lake, then rising onto Gokyo Ri’s steep slopes. A line of head torches already lights the trail ahead.

The usual afternoon cloud has arrived maddeningly early, quickening our step, though it’s still the slowest I’ve ever walked and the hardest I’ve ever breathed. Every few steps I stop for precious thin air, then race on in slow motion.

After about 90 minutes, the sight of prayer flags above me is truly a prayer answered: the summit is near. Snow tumbles across the mountain and my fingers and toes have turned wooden with cold. A man beside me complains of blurred vision in one eye as altitude sickness descends on him but on we plod, weaving through a metropolis of cairns to the summit, which is now blanketed in prayer flags and cloud.

Below us, the Ngozumpa Glacier carves its way through the mountains but every peak around it is hidden by cloud. I have climbed my Everest but there’s no view of the Everest I’ve come to see. Such is mountain life.-Andrew Bain travelled courtesy of World Expeditions.